The latest in a series of academic challenges to the New Urbanism turns out to be weak in all the areas that matter most, argues author Michael Mehaffy.

Some years ago, Harvard architecture professor Alex Krieger made one of the most memorable and withering critiques of the New Urbanism: in too many cases it was, he said, "sprawl in drag." What he meant was that the underlying patterns of sprawl were still dominating, and no mere repositioning of colorful traditional buildings on streetscapes would be enough to change that. While the Charter of the New Urbanism was much more thoroughgoing than Krieger suggested, the criticism was all too valid for a number of projects.

Since then, many New Urbanists – whether thus self-identified, or merely following the same set of Charter principles – have tried to do more to combat sprawl and its profligate waste of resources. And indeed, they've had notable successes building new urban districts in formerly declining inner cities, HOPE VI mixed-income housing projects, and new LEED-ND projects with good transit, district energy and other resource-conserving features (a new certification they helped to develop). While the magnitude of success is a subject of debate, there's clear evidence that these efforts are beginning to make a measurable difference on factors like carbon emissions.

The New New Urbanism

But the New Urbanism surely has its remaining flaws. Moreover, no good attempted deed goes unpunished among competitive designers nowadays. Thus a long series of competitors has arisen to the New Urbanism, each with their own attempted critiques – and each usually with some variation of the moniker "X" Urbanism: Everyday Urbanism, Real Urbanism, Now Urbanism, and so on. The one thing they have in common is the backhanded respect they pay to their competitor, suggesting that it's "the team to beat."

Most recently, Krieger himself has come forward with a number of colleagues, offering a new alternative that could better meet the design standards of the avant-garde: "Landscape urbanism." What is it? Krieger's associate Charles Waldheim, one of the originators of the concept, made clear its competitive nature: "Landscape Urbanism was specifically meant to provide an intellectual and practical alternative to the hegemony of the New Urbanism."

Charles Waldheim speaking to the UNC College of Arts and Architecture, Feb. 17, 2010.

More specifically, Landscape urbanism, according to Waldheim, rejects the New Urbanist idea that urban design can reform the auto-dominated patterns of the Twentieth Century, and their negative social and ecological consequences. It seeks to provide an alternative to the "prevailing discourse" that sees "a kind of 19th century image of the of the city, that said if we could put the toothpaste back in the tube of automobility, we could all get out of our cars, and live the right way, the kind of moral and just way, we could somehow reproduce some social justice and some environmental health that we feel as though we've lost."

Instead, according to leading LU theorist James Corner, we are to embrace surface, not form – and especially, the surfaces of sprawling cities: "Horizontality and sprawl in places like Los Angeles, Atlanta, Houston, San Jose, and the suburban fringes of most American cites is the new urban reality. As many theories of urbanism attempt to ignore this fact or retrofit it to new urbanism, landscape urbanism accepts it and tries to understand it."

How does this new understanding manifest itself? The LU schemes are often characterized by long fingers of lush green spaces forming fanciful abstract shapes. The designers are very clear that these shapes are not the product of such factors as walkability or transit or mixed use – the usual aspirations of New Urbanism – or of any other urban precedent. In fact they are soaring new fantasies, based on the most fanciful and arbitrary of generative forces. Here is Waldheim describing a scheme by Corner:

What I want to draw your eyes to are these lozenge shaped, weird football shaped public open and park spaces. Corner's proposition here would be that the shape of the public realm, the shape of the parks and the plazas and the open spaces, would not be derived by urban precedent from models of the 19th century, would not be derived by walking radii of transit oriented oriented development or other principles. It would be derived from a mapping of the plumes of the toxicity subsurface onsite.

Plumes of toxicity? Weird football shapes? Non-designers might be forgiven for wondering why designers would employ such arbitrary, even perhaps deranged forces, at the apparent expense of requirements for walkability, social interaction, access to transit, dynamics of public space – perhaps even social justice and equity. After all, there is no reason to suppose, say, that a frail or poor or elderly person can navigate such a vast no-man's land of space to access transit or other daily needs.

But the Landscape Urbanists accept horizontality (Corner), accept auto-dominated patterns (Waldheim) – accept sprawl. Hence the vast stretches of empty green space, obeying no laws of organization save the designer's fantasies. Here is Alan Berger, in an essay in Waldheim's book The Landscape Urbanism Reader:

The phrase "urban sprawl" and the rhetoric of pro- and anti-urban sprawl advocates all but obsolesce under the realization that there is no growth without waste. "Waste landscape" is an indicator of healthy urban growth.

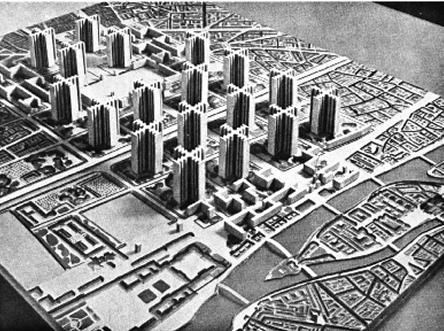

There is more than a faint echo here of Le Corbusier, in his highly influential 1935 book The Radiant City:

The cities will be part of the country; I shall live 30 miles from my office in one direction, under a pine tree; my secretary will live 30 miles away from it too, in the other direction, under another pine tree. We shall both have our own car. We shall use up tires, wear out road surfaces and gears, consume oil and gasoline. All of which will necessitate a great deal of work enough for all.

Le Corbusier's Radiant City.

Art Uber Alles

The Landscape Urbanists, like many free-market defenders of sprawl, seem to think that sprawl is the result of inexorable forces, and did not arise as a result of comprehensible historical choices – choices that can be understood and thereby, to some extent, changed. Indeed, both groups share a remarkable consistency in their laissez-faire attitudes to what is, and what cannot be changed through concerted public action.

Yet the historical record is clear, in the writings of Le Corbusier and others: sprawl was the result of designers' visions of their future, working with industrialists (or, less charitably, as apologists and marketers for industrialists).

Indeed, the Landscape Urbanists' shallow "understanding" of the forces that generated sprawl seem more aimed at constructing a "grand narrative" that declares that nothing is to be done, except to create art. History, precedent, typology – all of these are irrelevant now, and the only relevant force is their own imagination: "avant-gardist architectural practice, an interest in autonomy authorship."

This is a kind of artistic "magical thinking": we will draw a beautiful deer on the wall of the cave, and tomorrow we will surely have a wonderful dinner. We will make our cities into magical art, and tomorrow they will be wonderful to live in. As they say, good luck with that.

Jane Jacobs famously warned that the city must not be treated as a work of art. But a century of avant-garde designers has done exactly that – to the detriment of cities. By doing so, they've confused visual order with a deeper, intrinsic kind of order. That's the order that people create around them every day when they form social spaces, create small acts of ordering, solve small human problems.

From those small acts of ordering, larger urban patterns have emerged and evolved, forming clusters of re-usable information. Those are the patterns of the traditional city: not mere stylistic contrivances, but evolutionary adaptations to the transcendent needs of human beings. For New Urbanists, these patterns may re-used usefully today, under the right adaptive conditions. They should not be eschewed simply because they have been used in the past. This evolutionary problem-solving principle transcends human culture: a porpoise does not reject a dorsal fin pattern merely because the shark used it 300 million years earlier.

There is surely a place in our built environment – a privileged place, even -- for imagination, fantasy, and soaring works of art. But it must surely be integrated into the everyday evolving fabric of human life, and moreover it must accommodate and respect that fabric, in a way that is beneficial for quality of life – and in a way that serves to avert looming disaster. This must surely be the essential professional responsibility of any architect-urbanist.

The New Urbanism is a long way from perfect – stipulated – but it is taking seriously the need to advance and learn, and to incorporate more of the bottom-up approaches championed by Jacobs, Alexander and others. Moreover, it is taking seriously the causes of waste and unsustainability, and the steps designers – working in concert with others – can take to learn from and reverse their own and others' mistakes. Most importantly, the New Urbanists refuse to let the complexity of urbanism be reduced to a mere question of artistic style and novelty of imagination.

New Urbanists assert, especially, that the work of architect-urbanists must be informed by nature, and evolution, and history; and that this engagement must serve our well-being and perhaps even our survival, at least as a viable civilization. To believe otherwise seems dangerously close to the magical thinking of a dying culture. Let us hope such a dying culture is only a trendy but quickly passing one within the schools, and not a more global one.

Michael Mehaffy is the executive director of the Sustasis Foundation. Michael is the author of many journal papers and popular articles, as well as eleven book chapters, and he is a member of the editorial boards of three international research journals in sustainable urbanism. He serves as a consultant to governments, university research projects and others.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

In Urban Planning, AI Prompting Could be the New Design Thinking

Creativity has long been key to great urban design. What if we see AI as our new creative partner?

King County Supportive Housing Program Offers Hope for Unhoused Residents

The county is taking a ‘Housing First’ approach that prioritizes getting people into housing, then offering wraparound supportive services.

Researchers Use AI to Get Clearer Picture of US Housing

Analysts are using artificial intelligence to supercharge their research by allowing them to comb through data faster. Though these AI tools can be error prone, they save time and housing researchers are optimistic about the future.

Making Shared Micromobility More Inclusive

Cities and shared mobility system operators can do more to include people with disabilities in planning and operations, per a new report.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie