The booming desert city of Dubai had ridden high in recent years, but the downturn in the economy has stalled the ambitiously expanding city. Christopher Corbett, an American planner who's worked in the region for years, offers an introduction to Dubai that goes beyond the hype to reveal a vibrant and fascinating city at a very strange time in its history.

I'm a senior planner at the Dubai office of a large international consultant. When I arrived early last year, things were jumping. My company couldn't hire enough staff for all the active projects we had. Hundred-story skyscrapers and mega malls seemed to sprouting from the sand all around us. But I knew that I was late to the party and already by early Fall 2008 there were signs that the boom was coming to an end. Then the layoffs started. The first "unpaid leave" notices were passed out in our office on December 31st. I'm one of the lucky ones, still here after what had become a monthly ritual of ever more staff cuts. There's a hopeful feeling now that the worst may be over. Meantime, some say that it was good for the boom came to an end, at least so Dubai's infrastructure development could catch up.

As a planner it was fascinating to come back to Dubai again and see how the city had grown since my previous stay ten years earlier at a time when many of Dubai's now famous shopping malls, palm islands, and themed developments were just ideas on a drawing board. Two of the first really big buildings went up while I was here in 1999: the twin Emirates Towers, then the tallest buildings in the Middle East, and Burj Al-Arab, the famous sail-shaped "seven-star" hotel. These were Dubai's first 1,000-foot-plus skyscrapers, an advance guard of what was to come. During the years since, Dubai has seen a building boom like no other.

I'm writing to give a proper introduction to the city where I live and work, given partly to correct some misconceptions about Dubai -- a common one being the notion that Dubai is little more than an upstart Las Vegas alongside the Arabian Gulf. In reality, Dubai is a complex, multi-ethnic and multi-layered city, and far older than Las Vegas. (Actually, I can't understand the comparison at all, since there's no gambling here and the Dubai economy is far more diverse than tourism-based Las Vegas; with its large trade and financial sectors, the economic profile of Dubai is probably more similar to Hong Kong or Singapore or even Miami.)

Later, in another installment, I shall discuss some of the planning issues in Dubai that have arisen from all the super-charged growth, plus some of my experiences as a planner on the ground in this sometimes controversial, but never dull, city. Whatever one thinks of Dubai, it's a fascinating work place and a great laboratory for an urban planner.

Dubai and the UAE – A Brief Overview

With about 1.6 million residents, Dubai is the largest city in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), a confederation of seven emirates that extend along the coast at the southern end of the Arabian Gulf. Ninety miles down the coast from Dubai is Abu Dhabi, the federal capital and second-largest city in the country, with a population of about one million. It is also the largest city in Abu Dhabi Emirate, a West Virginia-sized expanse of sand that accounts for 86% of the total land area of the UAE. Along with reputedly the world's largest sand dunes, it is also where most of the oil, both off-shore and on-shore, is found.

The six remaining emirates, including Dubai itself, are essentially city states. Dubai Emirate, the second largest in area, though still only slightly larger than Rhode Island, is the most populous with about 2 million people. It extends 70 kilometers inland from the coast to a low but rugged mountain range. On the other side of the mountains is Fujeirah, the only emirate that faces the Indian Ocean. The fast-growing ports at Fujeirah and nearby Khor Fakkan capitalise on the fact that they are a full day closer by ship to the open ocean.

The urbanized portion of Dubai extends from the old central part of the city southward about 40 kilometers down the coast to the port at Jebel Ali, which within a few short years has grown to be the world's seventh largest container port. Most of the built-up areas of Dubai are within three-to-five kilometers of the coast, though isolated themed developments are encroaching ever farther into the desert, and as some would note, ever farther into the shallow waters of the Arabian Gulf.

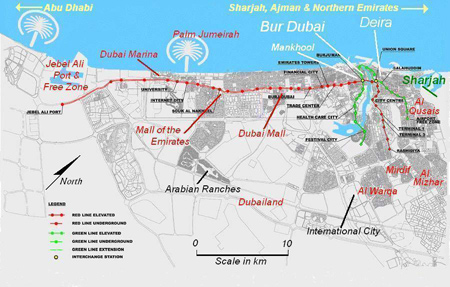

With most of the urbanized area hugging the coastal strip, Dubai remains a dense, linear city, making it ideal for rail transit. The Red Line (previously profiled on Planetizen), which opened with large crowds on September 9, parallels the coast for most of its 45-km distance. So far the trains are crowded, and ridership is likely to remain high for a number of reasons, one of which being that the Metro conveniently strings together several of Dubai's major activity centers which are strung out along the coastal strip.

North of Dubai are the smaller city-states of Sharjah, Ajman, Umm Al-Quwain, and Ras Al-Khaimah (collectively known as the Northern Emirates), all undergoing their own development booms. Dubai, Sharjah and Ajman together form a single urban area of about 3 million population, with continuous urban development extending 65 kilometers along the coastal strip from Ajman south all the way to Jebel Ali.

Sharjah, known for its more conservative ways along with its showcasing of Gulf Arab cultural heritage, is a densely-populated city right next door to Dubai. With its lower rents, Sharjah historically served as a bedroom community for tens of thousands of commuters working in Dubai, though with the weakening economy and falling rents, recently some Sharjans have been moving back to Dubai. During the boom, central Sharjah was transformed into a virtual forest of forty-story flats, many now standing unfinished. During the commute hours, traffic between the two cities barely moves. Recent estimates put the population of Sharjah at about 900,000 with another 400,000 in Ajman (as recently as 1980, Ajman had just 30,000 residents). Extension of the Metro northward to these towns, where many don't own cars, should seem like a no-brainer, but regrettably, Sharjah, Dubai, and Ajman all have a long history of ignoring one another. Sharjah is not even shown on most official maps of Dubai.

Central Dubai - Deira

The older "central" part of Dubai is actually situated near the northern extremity of Dubai proper, bordered by Sharjah to the north. Khor Dubai, locally known as "The Creek," is a salt-water inlet extending inland about 10 miles from the Arabian Gulf and divides central Dubai into two parts, Deira to the north and Bur Dubai on the south bank. The Creek itself is Dubai's most prominent natural feature, providing a scenic edge to the older central city neighbourhoods which crowd up to the waterfront along either side. The Creek is the scene of constant activity and local colour, with a continuous procession of passing yachts, motorboats, ferries, dhows, and abras. This is the old part of the city, a hub of trading activity dating back several hundred years. To this day, trade and commerce, not oil, are the main business of Dubai.

(Dhows are large wooden boats which ferry cargo back and forth across the southern Arabian Gulf between Dubai and Bandar Abbas, Iran's main southern port just 140 miles away; they've been doing this for centuries. Literally hundreds of dhows are docked along the north side of the central Dubai waterfront. Abras are water taxis, small open wooden boats, each holding about twenty passengers, which ferry tens of thousands of people across the Creek every day, passing dozens of dhows at anchor along the way. Despite their rustic look, they are actually operated by the RTA [Roads & Traffic Authority] and are an integral component of Dubai's public transit. )

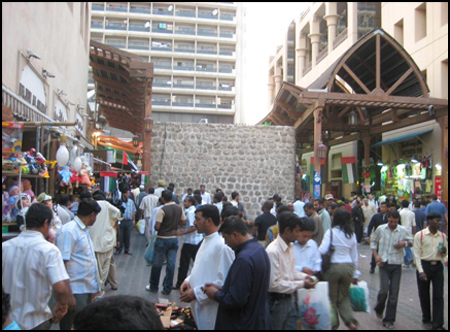

On the north side of the Creek is Deira, a dense warren of crowded streets and alleys containing several congested commercial and retail (souk) areas; Dubai's famous Gold Souk, the world's largest, is located here. The three hundred-plus gold shops line several arcaded pedestrian streets and attract gold buyers and tourists from all over the world.

Central Deira doubles as a densely-populated residential neighbourhood; multi-story buildings are packed together with crowded tenements occupying upper floors above ground-floor and mezzanine-level commercial establishments. Most residents are low-income families or single male labourers. Nearby, two-block-long Baniyas (or Bani Yas) Square is the only open space aside from the creekfront itself. It is currently torn up for construction of a Green Line Metro station. The streets are teeming with cars, buses, delivery trucks, bicycles, and pedestrians; as I long-ago learned the hard way, it's no place to drive a car into. The north side of the square used to be lined with shwarma stands, but most have been closed down in a misguided effort (in my opinion) on the part of the Municipality to sanitise the city for tourists. Baniyas Square used to be the commercial heart of Dubai, but with the opening of outlying office centers, commercial strips, and mega-malls, Baniyas has fallen out of favor and looks noticeably shabbier than it did 10 years ago.

At the south end of Deira, close to the Creek, is Deira City Centre, the first of Dubai's big shopping malls. Because it serves a large, densely-populated catchment area, City Centre remains the most consistently crowded of the big malls in Dubai, despite looking a bit dated compared to the glitzy new mega malls like Dubai Mall or Mall of the Emirates. It opened in 1994 and has been expanded several times since, but in the process has sucked some of the life out of Baniyas Square, the old commercial center just a couple kilometers away.

Further down the creek, moving away from Deira, is yet another shopping paradise called Festival City. It's an unusual mix of high-end mall (with a Venetian theme), hotels, and several big-box stores, notably Dubai's only IKEA (exactly like the one I shop at in Emeryville, California -- but with faster delivery!). Opposite IKEA is a mega-supermarket the size of a couple football fields called HyperPanda; both open onto a central atrium connecting to the mall. Festival City extends right down to the Creek with a pedestrian plaza fronting a boat marina; there are pedestrian promenades along the water as well as along a connecting circular canal that runs through the mall. For now, Festival City is in car country but a future extension of the Metro Green Line is already proposed, and I have no doubt that it will be built fairly soon.

Central Dubai - Bur Dubai

Across the water on the south bank of The Creek is Bur Dubai, a collection of neighbourhoods which fan out two or three kilometers toward the south away from the Creek. The areas closest to the Creek are very congested and contain some of Dubai's oldest districts and busiest souks. From my apartment located in the nearby Mankhool district, it's a fifteen-minute walk to the Bur Dubai waterfront where I can step onto an abra for the scenic, and sometimes bumpy, five-minute ride across the Creek to central Deira.

To get to the waterfront, one must walk through the Old Souk, as it's called, which is now mainly a market for textiles and clothing; it runs parallel to the Creek and has been spruced up in recent years by Dubai Municipality, restoring the original architecture. It's also a local tourist attraction, and on Fridays it's jammed with thousands of labourers on their weekly day off. Nearby is the Dubai Museum, which features exhibits of everyday life in old Dubai, built underneath an 18th-Century fort. A short walk away, next to the Creek, is Bastakia, a jumble of restored ancient buildings, notable for containing one of the largest collections of wind towers remaining in the Arabian Gulf.

My Neighbourhood – Mankhool

My apartment is about a mile away in a neighbourhood called Mankhool; the area is also commonly called Bur Juman, after a nearby shopping mall. From an urban design perspective, Mankhool is not very inviting a concrete jungle of 8-story (G+7) apartment buildings built very close to one another with no green space anywhere. However, the location is very central and thus popular for its convenience. During the cool season, Mankhool is easy walking distance to most of the central, and more interesting, parts of the city described above, and very close to supermarkets and other shops and services located right within the neighbourhood; the feeling is reminiscent of my years living in Manhattan. There are three Metro stations nearby, one already in operation, so I have no more excuses not to go anywhere on account of the traffic. (I had lived much of my life in places where rail transit was a given; the opening of the Metro in Dubai was my first experience of seeing a population suddenly liberated from the tyranny of cars.)

There is an undeveloped city block directly in front of my apartment, so from my top-floor flat I have an unobstructed view across the sand toward the city beyond (I had to pay three bribes to get this apartment during the boom last year). Kids play cricket down below, sharing the sandy plot with local dogs who poop on it. The empty city block is the only one left in the neighbourhood and would be perfect for a local park, as Mankhool has none. Unfortunately, the space will surely fill up with a couple more bulky G+7 apartment buildings, ignoring the fact that Dubai Municipality planning standards require a neighbourhood park for an area the size of Mankhool and this is the only undeveloped plot left to put it. A common justification for the lack of parks is that every building in this relatively high-rent neighbourhood has a rooftop swimming pool and gym. Nevertheless, a city-block-sized green space here would break up the monotony and provide a sorely-needed oasis in the middle of so much concrete and masonry.

Beyond the Centre – Sheikh Zayed Road, the Malls and the Coastal Corridor

Beyond Bur Dubai, Dubai extends another thirty kilometers southwesterly down the coast toward the port at Jebel Ali. Twelve-lane Sheikh Zayed Road is the main artery running the entire distance, and beyond Jebel Ali, the same road continues on for another hundred kilometers to Abu Dhabi (I did the 150-km commute -- each way -- every day last January while working at the Abu Dhabi office. This is considered one of the ten most dangerous roads in the world; there's no speed limit after crossing into Abu Dhabi Emirate, which quickly becomes fairly obvious).

Along with frontage roads, the Dubai portion of Sheikh Zayed Road measures a whopping 150-meters across (500 feet). This monster road parallels the coastline about two-kilometers inland; in between is Dubai's largest expanse of continuous urban development. It is mostly low-rise residential some quite suburban in character becoming more dense, urban, and commercial moving northward toward the city centre. Large expanses of this area, especially the Jumeira Beach neighbourhoods, are almost LA-like, reminiscent of Playa del Rey or Venice.

The Dubai Metro Red Line, running parallel along Sheikh Zayed Road, serves local catchment areas within the long coastal urban corridor with feeder bus lines terminating at each Metro station. Stations are located a mile apart, more-or-less, at major activity nodes like the big shopping malls (Dubai Mall; Mall of the Emirates) or at major employment centres (World Trade Centre; Dubai Financial Centre). The southern terminus at Jebel Ali Port and Free Zone (station not yet open) is Dubai's single largest employment centre; the area is a traffic nightmare along local stretches of Sheikh Zayed Road and its approaches, partly due to the enormous volume of truck traffic. There is a long-range plan to connect the Dubai and Abu Dhabi Metros.

Many of the high-rises frequently shown in the media, are located along either side of Sheikh Zayed Road or close to it. So are the two biggest shopping malls -- Mall of the Emirates, probably best known for Ski Dubai, and the newest and, for the moment, largest shopping mecca, simply called Dubai Mall. Located in the shadow of 2,685-foot high Burj Dubai (Dubai Tower), Dubai Mall has all the usual stuff: an ice rink, an aquarium, two huge food courts, plus an improbable 1,100 stores. Even Bloomingdales is getting in on the act, opening its first foreign outpost here, and I cannot neglect to mention that Dubai Mall has the only Fatburger in this part of the world, though like all the other Fatburger upstarts, not as good as the original on Santa Monica Blvd. in West Hollywood (sorry, this is another brand which went downhill when they started expanding).

Architecturally, the immense mall is fairly ordinary; admittedly, it's difficult to make such a huge space continuously interesting and intimate, but Dubai Mall doesn't lack for trying. There is one very good urban design element which does stand out however, and that is how the ground floor concourse, lined with restaurants and more shops, opens out on to an expansive pedestrian plaza and lagoon (instead of a US-style parking lot), anchored on the north side by the 160-floor, half-mile-high Burj Dubai (officially opening in January). The plaza itself surrounds an artificial lagoon lined with newly-constructed high-rises interspersed with mid-rise residential buildings. The architecture of the mid-rises is vaguely North African/Mediterranean; they are linked to the mall by a pedestrian bridge arching over the water. For all its huge size, the presence of Dubai Mall is not particularly overbearing, partly perhaps because the lagoon draws visual attention away from it. The entire precinct, known as Downtown or Old Town, functions as a large TOD, with cars hidden out of sight, lots of pedestrians milling about, and activity nodes all within sight and walking distance of one another as well as to a nearby Red Line Metro Station.

It's significant to point out that most of the big shopping malls in Dubai have placed car parking out-of-sight, either underneath or alongside, with multi-level parking structures typically incorporated into the architecture of the buildings so that they're not visually conspicuous. US-style suburban malls surrounded by oceans of parking are rare in Dubai, the ferocious summer heat being one reason for this. It shows that even the very largest big-box developments can be designed to do away with the sight of cars. Parking structures are more expensive upfront to build, but equally costly -- and way more unsightly -- is the paving over of dozens of acres of expensive real estate for parking.

Palm Jumeirah and Dubai Marina

There are dozens of residential and mixed-use developments in various stages of completion all across Dubai, but located along the main coastal corridor of Dubai are two major developments especially worth mentioning. These are Palm Jumeirah and nearby Dubai Marina.

Palm Jumeirah is a land-fill built in the shape of a palm tree which extends five kilometers offshore, located approximately 25-km down the coast from central Dubai. It has received a lot of international press and has become one of the iconic landmarks of Dubai. The trunk of the palm tree is a dense mini-city consisting of medium- and high rise buildings, most of which are residential, while the palm fronds are lined with expensive villas (single-family, detached houses), each with water frontage. At the end of the main spine is the famous -- some would say notorious -- Atlantis Hotel, scene of that $20-million opening party and fireworks extravaganza which made the cover of Newsweek last November. Running above the central median of the main spine road is an elevated monorail connecting the Atlantis with the mainland, with a planned extension to the Dubai Metro Red Line; until this is built, the monorail will not likely receive a lot of use, except by tourists perhaps.

Just to the south of the Palm Jumeirah is Dubai Marina, the biggest single new urban development anywhere in Dubai. Dubai Marina is basically a new city built along either side of a 2.5-km-long artificial waterway lined with high-rise buildings and boat marinas. It's an extremely dense development with residential buildings typically rising 40 to 60 floors, with at least two rising more than 100 stories, all spaced close together, forming a Manhattan-like montage. When complete, the artificial waterway will be lined with more than 200 high-rises overlooking, collectively, the world's largest marina. Public walkways line all waterways and beachfront areas.

Dubai Marina was being submitted as a concept plan to Dubai Municipality in early 1999 at a time when I was working there; I was asked to write up comments on this then-seemingly improbable project. Much of Dubai Marina is now built, and high-rise apartments here have become popular with high-income expat renters. Sheikh Zayed Road along with the Dubai Metro Red Line, runs right alongside Dubai Marina, with a soon-to-open Metro stop at a new mall, itself recently opened, simply called Marina Mall. Right across Sheikh Zayed Road (on the inland side) is yet another huge mega-project, called Jumeirah Lakes, where yet dozens more high-rise residential towers line the perimeter of an artificial lake.

The Inland Corridor

Dubai has a secondary corridor of development, perpendicular to the coastal strip, which extends inland approximately fifteen kilometers from central Deira. Extending inland, new suburban neighbourhoods fan out into the desert so that the corridor is no longer very linear. It is a part of Dubai tourists rarely see despite its proximity to Dubai International Airport (DXB). The second Metro line, the Green Line, due to open in June 2010, will serve some of the neighbourhoods within.

This inland corridor includes the Airport and the built-up areas that surround it, most notably a large expanse of fairly dense mixed-use and residential development which extend from the Airport several kilometers to the Sharjah boundary. Very few roads in these neighbourhoods (known as Al Twar and Al Qusais) extend across the Dubai-Sharjah boundary, resulting in traffic tie-ups on the roads that do exist. This is working-class Dubai (not to be confused with the labor camps). The neighbourhoods contain modest flats in low-rise buildings with blocks of light industrial and warehouse buildings interspersed throughout. Most streets do double duty as commercial strips.

At the southeast corner of this sprawling district is the infamous labor accommodation known as Sonapur, which has received a great deal of attention from the international press in recent years. It is the largest single labor village in Dubai, housing on about one square mile of land 300,000-400,000 workers (estimates vary), most from the Indian subcontinent. The "camps" consist mainly of concrete buildings and are provided by individual employers. Conditions vary from wretched to college dorm style; construction companies are notorious for providing the worst.

Beyond the Airport and Sonapur, the inland corridor extends further inland toward several large, low-rise suburban residential neighbourhoods bordering on the desert, sweeping around the southern end of Dubai Creek. The various, mostly planned neighbourhoods, including Al Mizhar, Mirdif, and Al Warqa, typically contain generous-sized detached houses, locally known as "villas". Many are inhabited by Emiratis, making this the largest concentration of Emiratis in Dubai, a city where they make up less than 20% of the total population.

Themed Developments in the Desert

There are a number of "themed" developments scattered across the desert, sometimes several kilometers distant from the main built-up areas of Dubai. Most are located along either side of an outer bypass called Emirates Road and include (in no particular order) Sports City, Arabian Ranches, Dubailand, Silicon Oasis, Academic City, and International City. They are in varying stages of development with Arabian Ranches and International City the most complete.

Relatively close-in International City consists of several thousand apartments housed inside dozens of medium-rise buildings, built in clusters named China, France, England, Italy, Morocco, etc., and is a popular option with renters on a budget. There are too few access roads so that traffic in and out of this development can be fearsome. There is also a conspicuous lack of supermarkets and other essential facilities and services within the development.

More distant is Arabian Ranches, which caters to the opposite end of the economic spectrum and (purposely) resembles a high-end subdivision outside of, say, Tucson, Arizona. Close by is Dubailand, a massive 110-square-kilometer tract of desert which, when completed, will consist of numerous themed sub-developments, notably including Arabian Ranches itself, and Falcon City of Wonders – featuring full-sized replicas of the Eiffel Tower, the Taj Mahal, and the Pyramids -- with themed residential communities surrounding each. Due to the current economic climate, some of these developments are "on hold."

All these places are located in car country and have received far more press than perhaps they deserve, given the press' penchant for latching on to whatever makes for the most outlandish story. It is likely, however, that some of the goofier projects will not survive the current financial shakeout, while others may be re-planned and/or scaled down a bit. The re-master planning of these developments could give local-based planners a lot of work to do in the years to come.

Postscript

Since this was written, Dubai's financial situation has become front-page news around the world. For those us working in Dubai, especially in the development sector (that would include planners), we have known about this for some time. Difficulties related to the payment of impending installments on debt by several large property developers in Dubai (notably US $3.5 billion Islamic bond coming due on December 14th owed by developer Nakheel) have been openly reported in the local press over the last several months, which makes me surprised that the financial markets around the word reacted as if they didn't know.

Part of my job as project planner is to collect payment on invoices submitted for our firm's work, so we are very close to the financial situation. The property market in Dubai began to slow down a year ago in the fall of 2008, in part as a reaction to the worldwide financial crisis whereby property markets were crashing everywhere from Las Vegas to Florida to Ireland to the Costa del Sol. Our workload suffered of course, as projects around Dubai were either closed down or put on hold. Over the course of the past year, our firm has let go half of its staff in the three Dubai-Sharjah offices, which is about typical for other firms involved with the development business in Dubai. Our remaining staff continues to work on various projects, however, mostly located elsewhere in the Gulf and Middle East region outside of Dubai.

The property market slowdown and financial situation in Dubai, especially as it relates to planning and the consulting business, will be discussed in more detail in a later installment discussing planning issues and how the planning process works in Dubai.

Christopher Corbett is Senior Master Planner and Acting Head of Master Planning for AECOM's Dubai office. This is the fourth time he's worked in the Middle East. He was previously with the Planning Department in the Ministry of Municipal Affairs in Doha-Qatar 1995-1998; then with CH2M-Hill in Dubai 1998-2000; and then with GHD (an Australian engineering consultancy) in Doha-Qatar during 2002-2003. During 2005-06, he worked for CDM in Louisiana on FEMA-sponsored post-Katrina community recovery planning and during 2007 for same in Greensburg-KS following destruction of the town by a May 2007 tornado. He has a Master's of Urban Planning from the Univ. of Washington in Seattle. His current USA home is San Francisco.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

In Urban Planning, AI Prompting Could be the New Design Thinking

Creativity has long been key to great urban design. What if we see AI as our new creative partner?

King County Supportive Housing Program Offers Hope for Unhoused Residents

The county is taking a ‘Housing First’ approach that prioritizes getting people into housing, then offering wraparound supportive services.

Researchers Use AI to Get Clearer Picture of US Housing

Analysts are using artificial intelligence to supercharge their research by allowing them to comb through data faster. Though these AI tools can be error prone, they save time and housing researchers are optimistic about the future.

Making Shared Micromobility More Inclusive

Cities and shared mobility system operators can do more to include people with disabilities in planning and operations, per a new report.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie