These are just a few of the ways Prof. Peter Bosselman of UC Berkeley analyzes the built environment in his latest book, Urban Transformation: Understanding City Design and Form. Julia Galef brings us this review.

Reading Peter Bosselmann's new book, Urban Transformation: Understanding City Design and Form, feels a little like being the Watson to an urban-minded Sherlock Holmes. Bosselmann's a professor of urban design at University of California-Berkeley and an expert city-sleuth, and it's fascinating to look over his shoulder as he scrutinizes the built form of cities for clues to how and why they change.

Exploring Copenhagen on foot in the chapter titled "Observe," Bosselmann notices for the first time the interdependence between the positioning of the city's churches and streets, as he looks up from a particular promenade to see the cupola of the Round Tower line up perfectly with the tower of the Church of Our Lady. That discovery sends him to the city's map rooms, where he confirms his suspicion that new additions in Copenhagen were carefully anchored within the existing angular geometry of the city plan. Later, he's struck by the unusual alignment of the Trinity and Holmen's churches. "The rotation provided a clue," he says, "that made me investigate the intent behind the many city extensions of the early seventeenth century." Further sleuthing reveals that Denmark's 17th-century king Christian IV rotated the churches to point towards his planned city expansions, signaling a shift in Copenhagen's center of gravity.

Bosselmann's explorations retain that feeling of discovery even when he moves from qualitative into quantitative territory. In "Measure," one of the book's strongest chapters, he walks the reader through his attempts to pin down some of the intangible aspects of urban morphology. What does "livability" really mean? What is a "sense of place"? It's a much more compelling approach than simply stating his findings up-front -- the reader gets to follow his trail of assumptions as they are formed, confounded by data, revised, and re-tested.

What emerges over the course of that chapter is how slippery the key concepts of urban design can be. It seems intuitive, for instance, that a strong sense of place has something to do with spatial enclosure, since "a more enclosed space brings people physically closer together," Bosselmann writes. But the evidence hasn't borne that out. After repeated failed attempts to demonstrate that relationship experimentally, Bosselmann concludes that "an emotional connectedness to physical space does not seem to depend on tightly spaced dimensions." His commitment to testing the field's seemingly common-sense assumptions rather than taking them for granted is refreshing, and all-too-rare. "Designers, like scientists, can be stubborn in holding on to their beliefs," he acknowledges.

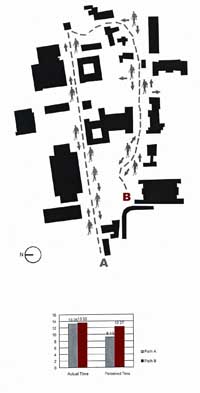

It is satisfying, however, when intuition is finally confirmed. In one series of experiments, Bosselmann's research team tries to quantify how various features of the built environment affect people's perception of time. They lead subjects on two paths through the Berkeley campus, with identical lengths and similar densities of pedestrians, but differing significantly in spatial complexity. Their subjects deemed the more circuitous walk with finer spatial dimensions to be more enjoyable and satisfying, but estimated it to have lasted much longer – almost 50% longer than the actual time elapsed. The finding echoes a sentiment expressed by psychologist and philosopher William James in 1892: "A time filled with varied and interesting experiences seems short in passing, but long as we look back. On the other hand a tract of time empty of experiences seems long in passing, but in retrospect short."

Bosselmann's temporal approach to urban morphology recalls what Gordon Cullen, in his influential 1961 classic Townscape, dubbed "serial vision": the way the city reveals itself to a person moving through it, each view being experienced in the context of the previous one. It's a particularly important concept for a city like Bosselmann's San Francisco, whose topography infuses its built form with powerful qualities that can only be understood temporally: the roller-coaster experience of following a street down into a valley and up again; the feeling of "mastery" when a street travels along a ridge, yielding views down the slopes on both sides; the anticipation that builds on the approach to a saddle-point (a gap in a ridge), giving way to an uplifting sense of arrival as the saddle is reached and a vista opens up of the next district or bay.

It's notoriously difficult to convey those experiential qualities of urban form in a model, and in the book's later chapters, Bosselmann explores what that means for the way we plan future development. A static model tells us nothing, for example, about how to situate buildings so that they will appear well-spaced to a driver approaching San Francisco via the iconic Bay Bridge. "Only an animated simulation shown in motion can demonstrate the importance of adequate tower separation," argues Bosselmann. "The proper separation will avoid creating a wall and blocking views of the skyline and the hills beyond."

Renderings of tall buildings are especially problematic. Portraying towers in elevation, from a distant vantage point, they give no sense of how the proposed buildings will appear to the pedestrian at ground-level, who will need to tilt his head back to take in their entire height. "Single station point perspectives are very misleading when it comes to showing large structures in one view," Bosselmann warns. "They seriously understate the true size of buildings."

Fans of maps and diagrams will geek out over Urban Transformation's copious graphics, many of which are in full-color. The figures are especially effective at illustrating the processes of change on which Bosselmann focuses, showing the serial views of San Francisco's skyline from successive points on the Bay Bridge; the after-images of people who stopped to linger in a public space for varying lengths of time; or the evolution of the figure-ground pattern of a block over the decades as buildings are built, consolidated, demolished, and re-built.

Julia Galef writes about urban design and development for Project for Public Spaces, The Architect's Newspaper, Metropolis and The Architects' Journal.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

San Antonio and Austin are Fusing Into one Massive Megaregion

The region spanning the two central Texas cities is growing fast, posing challenges for local infrastructure and water supplies.

Since Zion's Shuttles Went Electric “The Smog is Gone”

Visitors to Zion National Park can enjoy the canyon via the nation’s first fully electric park shuttle system.

Trump Distributing DOT Safety Funds at 1/10 Rate of Biden

Funds for Safe Streets and other transportation safety and equity programs are being held up by administrative reviews and conflicts with the Trump administration’s priorities.

German Cities Subsidize Taxis for Women Amid Wave of Violence

Free or low-cost taxi rides can help women navigate cities more safely, but critics say the programs don't address the root causes of violence against women.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie