Cities need more “missing middle” housing. A new startup aims to help real estate developers build it.

This is a guest blog post by Hugh McFall republished from Moonshot.

I have lived in San Francisco for over seven years, including in the neighborhood of Cole Valley, which is tucked beside Golden Gate Park and home to Victorian style row houses and apartments. Recently, an unusual sight appeared in the neighborhood, something that I hadn’t previously seen in this area: a construction crane.

Cranes and construction sites are a fixture in many growing cities, so it’s not typically something worth noting. But they rarely appear in most pockets of San Francisco, a city in dire need of new housing construction. This particular crane towers over what will become 160 units of affordable housing, and the development checks all of the boxes: it turns a vacant lot into housing in a densely populated, walkable neighborhood. It sits beside grocery stores, cafes, parks, and public transportation.

There is a growing sense that this is the right approach to building our way out of a housing crisis: a report from UC Berkeley found that “infill housing development” — building on existing land within a city — could drive both $800 million annual economic growth and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 1.79 million tons in California, compared to the business-as-usual approach of suburban development.

So why don’t we see more projects like this in the cities that so desperately need it? The answer, oftentimes, is that it’s incredibly difficult to get the approvals to build infill housing in cities across North America. In particular, it’s because much of the land is zoned only for building single family homes, and it’s illegal to build anything else.

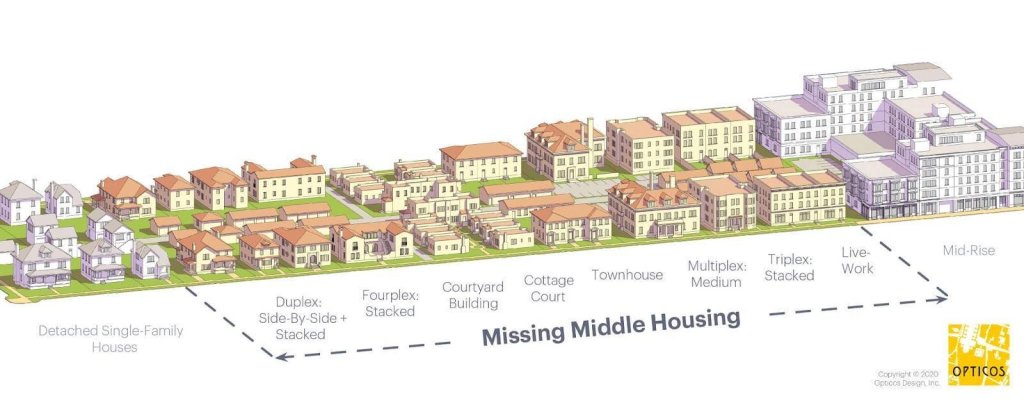

The U.S. is short approximately 1.5 million homes, according to the National Homebuilders Association. But it’s not just the lack of housing that’s an issue, it’s also the way that a lot of housing tends to get built: if it’s not a condo skyscraper that you can only find downtown, it’s sprawl out into suburbia. This is further from where many people want to live and work, and it creates a bigger environmental footprint by making people more dependent on cars. In recent years, this has created what’s become known as a “missing middle” in our housing supply.

The term “missing middle housing” was coined in 2010 by Daniel Parolek, an urban designer, architect, and owner of the firm Opticos Design. He defines “missing middle” as multi-unit or clustered housing types that are similar in scale to single-family homes: think townhomes and row houses, more Brooklyn brownstone than Manhattan skyscraper.

Opticos was the firm that designed Culdesac, a car-free neighborhood in Tempe, Arizona, a good example of missing middle housing and walkable neighborhoods. Missing middle housing is meant to be built densely within a city, as an infill development similar to the affordable housing project in San Francisco.

This type of housing was common in cities across North America before the 1940s, and then the automobile reoriented cities to fit its image. There are signs, though, that cities in the U.S. and Canada are looking to build more missing middle housing once again. Minneapolis, for example, abolished single-family zoning in 2019, so you can now build a duplex or triplex in any neighborhood in the city. Vancouver recently made it possible to build duplexes in any residential neighborhood. In San Francisco, there is a push for infill development to add housing near transit and jobs, helping cut down commutes and sprawl.

“From an urban planning and municipal planning scale, a number of American cities are moving away from single family zoning and towards denser multifamily zoning,” Kyle Vansice, the Founder & CEO of Cedar told me in an interview with the Cedar team. But, in Vansice’s view, they are not moving fast enough — and Cedar is hoping their software can help speed things up.

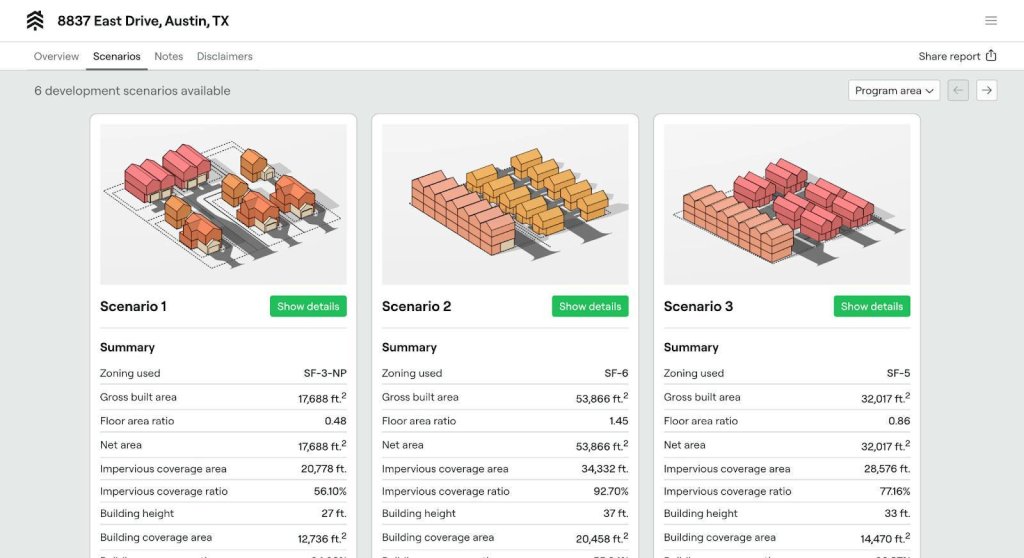

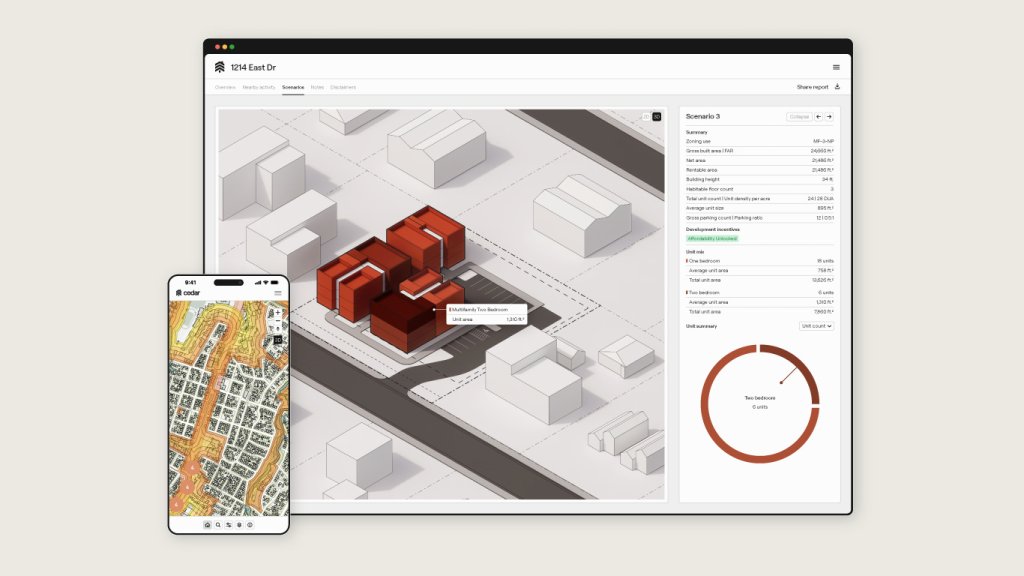

Cedar’s focus is helping real estate developers figure out how to build more missing middle housing within cities, rather than sprawling outwards. They help developers navigate all the red tape and complexities of building within a city — especially zoning, land development codes, permits, and incentives — and quickly understand if any given site is feasible to build on.

These regulations are what the Cedar team calls the “invisible force fields” that affect the world around us, and what we build on it. Once a developer understands the regulations on any given site, Cedar then provides a catalog of different housing types and generative design tools for their customers to do early conceptual project planning, helping them find opportunities to build that they may not have had the time or resources to do on their own.

Vansice co-founded Cedar in 2022 alongside Nate Peters and Rahul Attraya. The trio, based in Austin, Texas, are classmates from architecture school and spent time in different parts of the design and technology industries: Vansice and Attraya worked at architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merril (SOM), and Peters built generative design software at Autodesk.

“Throughout our careers, our focus was on complexity and scale. Taller buildings, the design of new cities, more efficient structural systems for landmark projects,” Vansice told me. He felt that while these were well-known projects — SOM designed One World Trade Center in New York, for example — they weren’t driving the type of systemic impact that they wanted to make. The projects they designed were “for a very small percentage of the world,” Vansice said.

The pandemic inspired some soul searching among the trio. “During the pandemic, we questioned whether our expertise in generative design and the built environment should be focused towards more pressing problems,” Rahul Attraya, Cedar’s chief operating officer, said.

They landed on the housing crisis. “It was very obvious that housing was that more exciting problem to us,” Vansice told me. “We realized that while housing represents 80-90% of our city's land area, very little design and almost no software has been directed at the development of our neighborhoods. If you want to design better cities, start with housing and neighborhoods. They are the fundamental building block.”

In most cities, feasibility, design, and permitting often takes longer than the housing construction process. It often takes over 6 months to complete feasibility, site planning, and permitting. Cedar aims to reduce this to a matter of days, which would make it easier and faster to build the types of housing that Vansice and his team would like to see more of.

Developers can take a plot of land and put it in Cedar’s platform to explore their options and different scenarios: whether they should build a low-density development of single family homes with accessory dwelling units, or mixed use multi-family properties that can house more people, for example. Developers can view each of these scenarios, understand the tradeoffs, and get to the right answer faster. Cedar is in its early stages — the company raised a $3 million seed round in late 2023 — but has already helped over 150 developers in Austin, the fastest-growing city in the United States. It plans to expand to more cities across the country.

What strikes me about technology like what Cedar is building is that it’s not impartial. It has a very clear stance on what the future of our cities should be, how developers should build, and what the result should be: new housing within city limits, densifying neighborhoods to create more walkable, affordable, and family-friendly communities. “Cedar is a bet on the future of North American cities,” Vansice said. “We’re making a bet that the era of single-family zoning that drives endless sprawl is not economically or environmentally sustainable any longer.”

They may be correct. The U.S. has a lot of homes to build, and there is a growing chorus that moving beyond single-family zoning will help us get there. “We're not going to overcome this deficit anytime soon just building single-family housing,” Ryan McCullough, managing director at Hines, a global real estate developer, told Axios.

There are other approaches, such as 3D printing homes and offsite modular construction, that aim to address the housing crisis as well. While promising, so far these efforts have offered more headlines than impact. The bankruptcy of Veev, a prefab home builder that raised over $600 million before abruptly shutting down last year after failing to raise capital, is a recent example of how difficult it is to transform the way we build, especially for companies seeking venture capital-scale returns. What Cedar is offering is a more prosaic, though potentially more impactful solution: helping smaller-scale developers to build more missing middle housing across the U.S., making it easier to build more sustainable communities in a country that sorely needs them.

Cedar is, however, one piece in a much larger puzzle. Its software can help developers move more efficiently through regulations and red tape, but they’re ultimately still limited by zoning and land development codes. They can help developers run faster, in other words, but they can’t change the rules of the game. Infill development also has its share of detractors, both from the “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) crowd of homeowners worried about their property values, and policymakers and activists concerned with gentrification or displacement of existing residents. Infill development has many benefits, but the difficulty is ensuring it’s done fairly and properly.

This underscores what’s both challenging and compelling about the housing crisis: it is deeply interconnected with other issues. Where we live influences so much of the course of our life: where we work, how healthy we are, who we become friends with, and more. At a bigger scale, it’s becoming clear that the way we plan and design cities is not only causing the housing crisis, it’s also deeply linked to climate change and our ability to address it. “The thing behind so many societal problems that we're facing now — housing affordability and the climate crisis, health issues, infinite sprawl — it all kind of comes back to that we don't build enough housing relative to other countries at our level of development,” Nate Peters, Cedar’s chief technology officer, told me. “It’s fascinating how far the wave ripples outwards.”

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

In Urban Planning, AI Prompting Could be the New Design Thinking

Creativity has long been key to great urban design. What if we see AI as our new creative partner?

King County Supportive Housing Program Offers Hope for Unhoused Residents

The county is taking a ‘Housing First’ approach that prioritizes getting people into housing, then offering wraparound supportive services.

Researchers Use AI to Get Clearer Picture of US Housing

Analysts are using artificial intelligence to supercharge their research by allowing them to comb through data faster. Though these AI tools can be error prone, they save time and housing researchers are optimistic about the future.

Making Shared Micromobility More Inclusive

Cities and shared mobility system operators can do more to include people with disabilities in planning and operations, per a new report.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie