While the Urban Transect promotes the city's coherence with respect to density and massing quite well, it does not promote a coherence with respect to the appearance of buildings. Dino Marcantonio presents a Transect which describes status, which he calls the Iconographic Transect.

The Urban Transect (Fig. 1), as developed by Andres Duany, is an excellent tool: it is a superior alternative to the failed model of mono-functional zoning, and it promotes a city's coherence with respect to density and massing. The historical record of cities that are both practical and beautiful confirms it as a viable model.

The Urban Transect (Fig. 1), as developed by Andres Duany, is an excellent tool: it is a superior alternative to the failed model of mono-functional zoning, and it promotes a city's coherence with respect to density and massing. The historical record of cities that are both practical and beautiful confirms it as a viable model.

The historical record, however, shows us still more than can be accounted for in the Urban Transect. For the cities that we love so much today--Rome, Venice, Prague, St. Petersburg, Charleston--also evince a coherence with respect to the appearance of buildings. What is needed is a tool that allows us to analyze and prescribe this coherence.

The historical record shows that buildings naturally represent the importance and purpose of the institutions they house, and they do this principally by relating to one another, i.e., more important buildings will tend to have more iconography and more specific iconography than lesser buildings.

When I use the term "iconography" I refer to the whole body of symbols which are intelligible to a particular people: everything from the Scales of Justice which we usually find outside a courthouse, to coats of arms, to architectural moldings and ornaments.

A city's courthouse is usually one of its more important buildings. Consequently we usually find that it is among the more richly ornamented buildings in the city: the architecture is more finely elaborated, and the non-architectural iconography is more lavish and more specific--a sculpture of Justice personified, the seal of the governing authority, etc.

In contrast, the house of a middle-class citizen is comparatively less important. Hence, the iconography, both architectural and non-architectural, is less elaborate and less specific--often no more than a pineapple over the front entrance to symbolize domestic hospitality.

As different as they are, both the courthouse and middle-class house appear to belong to the same family, however. One could form a decent picture of the character of a place by lining up all the representative buildings in order from most important to least, and then taking "core samples." Fig. 2 describes the character of some imaginary generic place (it is not a specific prescription). I have repeated the door surround motif to highlight the continuity across the diagram.

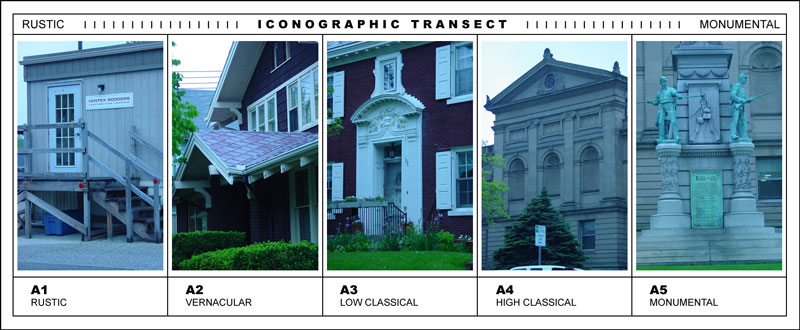

In short, this diagram attempts to do with iconography what the Urban Transect does with plan and massing. Hence I call it the Iconographic Transect. I have found a division into five categories to be useful: Monumental; High Classical; Low Classical; Vernacular; and Rustic.

Fig. 2 – The Iconographic Transect

Here I should add that I define the terms "vernacular" and "classical" in a particular way. Vernacular architecture is architecture which makes use of the architectural forms which have been handed down for generations in a particular culture of a particular place, and construction techniques which have been handed down.

Classical architecture is that segment of the body of traditional architecture of a people which has achieved the highest, most articulate, and most refined expression. (Despite Fig 2, I am not using the term "classical" here to suggest exclusively the more refined forms of the Greco-roman tradition.) We can define "rustic" for our purposes here as construction which is entirely pragmatic and utterly devoid of iconography.

The Iconographic Transect can be applied to all cultures and all places that have developed an intelligible iconographic corpus that is harnessed in the building of cities. Thus, to some extent, any place can be diagrammed to define roughly the character of that place. South Bend and Venice each have a very different set of traditions which set up expectations and render certain conventions intelligible. What is understood in South Bend may not be understood in Venice, and vice versa. Thus, each has a unique diagram. Fig. 3 shows an Iconographic Transect for South Bend, Indiana.

Fig. 3 – The Iconographic Transect of South Bend

When one brings the Iconographic Transect and the Urban Transect together on X and Y axes to form a chart, one can begin to diagram a place more completely. Plan and elevation are both accounted for. Building types can also be located in a way which more fully describes their meaning for a community. A government building will be centrally located (according to the Urban Transect), and will be more fully ornamented than a single family house (according to the Iconographic Transect), for example. The Transect Chart (Fig. 4) might describe a typical American city today.

Fig. 4 – The Transect Chart

Every place and time will have a different chart as differing peoples will value their institutions differently, and a people's values will change over time. Fourth-century Rome, for example, would have a very different chart. As it was still predominantly pagan, Christian churches were placed on the outskirts of the city and very modestly decorated: in A2/T3 or A3/T3. Pagan temples, in contrast, were situated in A4/T5 and A4/T6. As centuries passed and Christianity became dominant, church buildings moved into the center of the city, and were decorated more lavishly, slowly coming to occupy the A4/T5 and A4/T6 slots.

The chart, like the architecture and urbanism which it represents, reveals what a people value. Here is an aspect of traditional urbanism which the New Urbanism is well placed to recover. We ought to be able to look at our cities and see who we are carved in wood and stone, for our own edification, and for that of our children.

Dino Marcantonio is Assistant Professor of Architecture at the University of Notre Dame, and principal of Marcantonio Architects.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

Amtrak Cutting Jobs, Funding to High-Speed Rail

The agency plans to cut 10 percent of its workforce and has confirmed it will not fund new high-speed rail projects.

Ohio Forces Data Centers to Prepay for Power

Utilities are calling on states to hold data center operators responsible for new energy demands to prevent leaving consumers on the hook for their bills.

MARTA CEO Steps Down Amid Citizenship Concerns

MARTA’s board announced Thursday that its chief, who is from Canada, is resigning due to questions about his immigration status.

Silicon Valley ‘Bike Superhighway’ Awarded $14M State Grant

A Caltrans grant brings the 10-mile Central Bikeway project connecting Santa Clara and East San Jose closer to fruition.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Caltrans

City of Fort Worth

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie