Despite the investments required of a design charrette, Robert Freedman makes the case that the process can save time and money on complex projects by way of three primary benefits.

When I returned to Toronto in 2002, after a dozen years working as an urban design consultant in the United States, I couldn’t believe how long and often confrontational the development approval process was here in Ontario. A large condo tower could take over a year and a half to wend its way through the bureaucratic maze —only to be rejected by angry residents and cautious councilors at the last minute. By contrast, while working in the United States—with Pittsburgh-based Urban Design Associates (UDA)—I found that the majority of our development proposals moved through the system and gained final approval with relative ease. Part of our success in the United States could be attributed to the fact that we often worked in inner-city neighbourhoods, where years of disinvestment created a hunger for new development. However, our projects in newer suburban communities met with the same levels of success. The main reason for our high rate of approval in the United States was, I believe, our commitment to community engagement. The majority of our projects included a multi-day design charrette that allowed us to work through a series of design alternatives before reaching consensus on the final plan.

City of Toronto - Planning - Urban Design

Photo Credit: Robert Freedman

The term charrette is thought to have originated at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris in the late 1800s. It literally means “little cart.” The story is that during the end-of-term assignments, design students worked day and night for several days to complete their work and, when the time was up, a bell would ring and someone would wheel the charrette through the studio to collect the final drawings. Some students, eager to complete a drawing, would jump onto the cart and continue working until the very last moment. Today the term charrette is used to describe an intense, multi-day design exercise—typically held in the community with a broad range of stakeholders—to help create a plan for a particular site, area, or neighbourhood. The term captures the spirit of the frenetic, creative, energy displayed by the students at the Ecole.

In Toronto, charrettes are seldom used and—other than a small number of progressive developers eager to work with their constituents—the majority of developers submit their applications to City Hall with very little public or staff input. (As it turns out there are some compelling economic reasons for preceding this way, but more on that later.) A public meeting soon follows, during which the applicant or their architect introduces the project to a room full of anxious area residents and business owners. The room is set up theater-style and the presentation is designed to impress—complete with beautifully rendered, 3-D marketing images that make it appear as if the building already exists. The message delivered: “Here’s what we’re building, and it’s a great addition to the neighbourhood. We like it, our customers like it, and we think you’re going to like it too. We welcome your comments (but only those that involve no substantive changes).”

All too often, especially where tall buildings are proposed proximate to single-family neighbourhoods, the community reacts with rage. Regardless of the merit of the proposal, some audience members will be furious simply because they have been excluded from the design process. To hear that a development is coming to your neighborhood is one thing, but it’s quite another to learn that it’s several magnitudes larger than anything you’ve anticipated—or think is reasonable. It’s basic human psychology: “How dare you propose this in my neighbourhood without asking me what I think? (Worth noting: the audience at a public meeting does not always represent the whole community. Those who don’t care or who welcome change don’t bother to show up. Nevertheless, a well-organized, vocal minority can wreak havoc on a project schedule.)

Whenever I hear frustrated and furious comments at a public meeting, I can’t help thinking that a design charrette could have prevented the friction and animosity entirely. Charrettes are as much about discourse as they are about design. It’s not enough to show the audience what you plan to build—you need to involve them in the creative process and give them a chance to understand the by-laws, design guidelines, and precedents that will influence what has, and can be, built in the area. With that knowledge they can then consider and work-through multiple possibilities before agreeing on a solution. I know from experience that charrettes provide a framework for all of this to happen—and they succeed.

So if charrettes work, why don’t developers and planners use them more often? One reason has to do with the historically confrontational nature of the development review process in Ontario. In a hot real estate market (and the condo-market in the Greater Toronto Area has been on fire for most of the last decade), there is enormous pressure on developers to get to market fast. Those who move quickly compete most effectively on price—and the small-unit (first-time-buyer and investor) market is extremely price sensitive. Working closely with the community may ultimately bring about the best result for everyone, but many developers perceive the process as too time consuming in this faced-paced, first-to-market environment. It may be simpler (and faster, as they believe) to just push forward with the plan and, if they can’t gain the approval of council, to appeal the decision and battle it out at the Ontario Municipal Board (OMB), (the provincial, quasi-judicial body tasked with reviewing municipal planning and development decisions). Neighbourhood opposition has become part of the development process in Ontario. Most developers hire a lawyer before they hire their architect and include funding for an OMB appeal in their budget. Adding a labour intensive (read: expensive) charrette as another line on the pro-forma doesn’t make obvious economic sense.

Despite these rational economic arguments, I am convinced that under the right circumstances the design charrette actually saves time and money. In addition, design charrettes build the kind of trust and social capital with residents and politicians that ultimately reduce the friction on future development debates. As in any negotiation, a charrette can only be successful if all parties recognize that their interests are best served by willingly participating and acting in good faith. To ensure the charrette provides a forum for reasonable discussion, the developer can set a density target and timetable as pre-conditions to participating. If all parties agree to the pre-conditions, then they come to the table knowing the rules and willing to work on those terms.

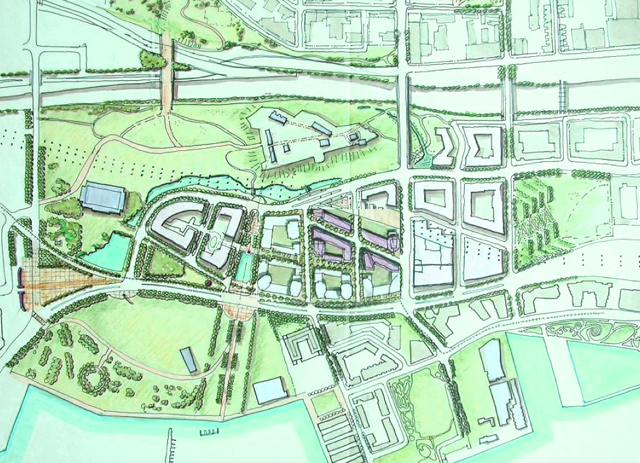

Fort York Neighbourhood Charrette - 2003 - Final Presentation Drawing

City of Toronto - Planning - Urban Design

Drawing by Charrette Participants (Design Team Leads - Urban Design, USI, dtah, Quadrangle)

Charrettes succeed for three main reasons. First, charrettes avoid what I would call the “assembly line” development review process. In a typical review everything proceeds from one step to the next in a roughly linear fashion. Once submitted, drawings circulate to the various city divisions, staff provide comments, statutory public meetings are held, a report is compiled and submitted to council, and council makes a decision. With large, mixed-use developments, this process might take 18 adversarial months or more. Application drawings, submitted to the city in multiple paper copies (the conversion to electronic drawing submissions has begun but remains painfully slow) are distributed to each of the commenting divisions where staff—most often in isolation—review and comment on the package before passing it on to the next group. Under this arrangement, those providing comments never get to hear or see the “big picture” from the design team, and they rarely get to hear what their fellow city staffers think. Inadvertently, groups within a division could provide contradictory comments, which confound (or more likely infuriate) the applicant.

By contrast, a design charrette is non-linear. Instead of a drawn-out, step-by-step process, the charrette is an intense, multi-day design mash-up. Wonderful things happen when you lock people in a room for two or three days with coffee and magic markers (and it’s not just the caffeine and marker-fumes). Ideally, the charrette takes place near the proposed development site, say in a church basement or school gym. The design team leads, but in the best charrettes everyone participates. The design evolves organically with input from all “stakeholders”—planning jargon that refers to everyone from developers and area residents to city staff, designers, business owners, politicians, teachers, and even police officers. All participants have a voice, and over the course of the charrette all points of view are aired. In the moment, people react, ask questions, and those with the answers are there to respond. There’s a swirl of activity. Drawings and models—not just words—become the tools of engagement. The designers articulate the reasons for making certain design decisions, and disagreements can be raised and resolved in real time—no need to wait for weeks for someone to answer a call or respond to an email.

The second reason charrettes succeed is that they provide early answers to critical design decisions—thereby avoiding expensive backtracking later in the process. They allow for meaningful feedback and comments early in the review process, when the project is still in the schematic design phase and changes can be made easily and without great expense. As we have seen, in a typical development review, the design team creates a near-finished-looking plan, complete with glossy drawings and models, and presents it to the neighbourhood at a public meeting. The neighbours want to talk about substantive issues such as tower location, height, and massing, while the applicant attempts to steer the discussion toward the finishing touches like materials, colours, and signage. The time for meaningful design input is long past. With a charrette, the community has several opportunities to weigh in and resolve issues at the appropriate time. Much easier to move a condo tower from one part of the site to another on a rough sketch or working model—than when the drawings are in design development and the building is half-sold. (In Canada, aggressive marketing and sales start early, because Canadian lending regulations require that 70 percent to 80 percent of units must be pre-sold to obtain financing). Pre-sales may be slightly delayed by the charrette—but afterwards the marketing team moves forward on a more solid foundation. In addition, the charrette reduces the overall time it takes to get development approval because the staff members in charge of the review have been involved throughout and the major issues have been raised and resolved.

Finally, charrettes work because they provide an ideal environment for gaining trust, exploring design alternatives, and reaching consensus. The design process always involves testing and refining alternatives as a way of distilling the best ideas down to their essence and arriving at the preferred plan. Unfortunately, in a typical development process, this fascinating and creative process takes place behind closed doors. Other than the project team, no one gets to see it or to take part in the discussions about why one idea was rejected and another preferred. At a charrette, the participants not only get to hear those discussions, they are invited to play an active role in creating the designs. The design process is complex, with many factors influencing what can ultimately be built, including by-laws, design guidelines, precedent, and architectural style. It takes time and energy to educate residents about why, for example, an area that is zoned for ten-storey buildings may in fact be suitable for buildings four or five times that height. During a charrette the reasons can be explained, precedents reviewed, and questions answered. Nothing happens behind closed doors. The process unfolds in the open and results in both a consensus plan and a well-informed group of participants. The charrette’s power lies in the convergence of information and creative energy.

Most successful charrettes begin not with an examination of preliminary development schemes but rather with a detailed exploration of the site and the surrounding neighbourhood using analysis drawings (what UDA calls X-ray Diagrams™) that focus on one or two pieces of critical information. If the building is to fit comfortably in its surroundings, the designers need to fully understand the context. As founding UDA Principal Ray Gindroz describes it, creating hand-drawn diagrams is like taking a walk through the neighbourhood with your pencil. The value is as much, or more, about what you learn by creating the drawing as it is about the drawing itself.

Once we have collectively explored and understood the underlying context, the real design work can begin. The well-run charrette includes a “charrette kit,” complete with enough black pens, coloured markers, tracing paper, scales, and spare model parts for all participants. As charrette leader, I divide the group into teams and assign the tasks, starting with a neighbourhood circulation plan and then moving on to preliminary site plans and building designs. When asked to draw, most adults protest and say they can’t. But when you hand them a marker—or set them up in front of a model—most quickly lose their inhibitions and get to work. It’s one thing to provide people with an opportunity to criticize a design that has been presented to them at the front of an auditorium. It’s quite another to gather around a drawing or model and to ask someone to show you how they would make the design better.

Weston Design Charrette, 2011, City of Toronto, ULI, Metrolinx - Photo Credit: Robert Freedman

Charrettes typically culminate in a public meeting on the evening of the last day. As the deadline looms, the teams scramble to complete their drawings and models—adding colour and thickening lines to ensure they can be seen from the back of the room. The moment arrives, additional community members stream into the auditorium, and the lights go down. One by one, leaders from each team stand up and present their thoughts and designs before the assembled audience. What they’re seeing on the screen is not a marketing presentation, but rather the rough sketches, drawings, and models they have helped to create over the past couple of days. If there are questions, more often than not, a participant rather than a member of the design team answers them. In a successful charrette, every stakeholder feels a direct connection to the images at the front of the room. There’s a true sense of ownership. Participants now have a stake—a vested interest—in the success of the plan.

So charrettes work, but they are also incredibly labour intensive. I am well aware of the time constraints faced by city staffers who juggle multiple applications simultaneously and the financial concerns of developers in this risky and competitive business. No city can organize itself and its staff to take part in charrettes on each and every application. However, all cities should be organized to support and staff charrettes on key projects, and developers and their design teams should be prepared to run them. On projects of citywide significance, facing potentially hostile community opposition, a well-run charrette ultimately saves everyone time.

Charrettes lead to better designs, better neighbourhood fit, much greater community buy-in, and better long term working relationships among all participants. Charrettes provide a successful method for reaching consensus and avoiding a costly appeal that has little to do with design. All parties affected by development decisions should give the charrette a very careful second look as a tool for achieving better planning and design outcomes.

Robert Freedman, MRAIC, AICP, LSUC, is the former director of urban design for the city of Toronto and current principal of Freedman Urban Solutions—an urban design, planning and development consulting firm based in Toronto. Robert has a multi-disciplinary background with degrees in architecture, planning, and law and over 25 years of experience working in a variety of urban and suburban environments in cities across the United States and Canada. [www.urbansolns.com, @FreedmanToronto, @UrbanSolns]

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

Amtrak Cutting Jobs, Funding to High-Speed Rail

The agency plans to cut 10 percent of its workforce and has confirmed it will not fund new high-speed rail projects.

Ohio Forces Data Centers to Prepay for Power

Utilities are calling on states to hold data center operators responsible for new energy demands to prevent leaving consumers on the hook for their bills.

MARTA CEO Steps Down Amid Citizenship Concerns

MARTA’s board announced Thursday that its chief, who is from Canada, is resigning due to questions about his immigration status.

Silicon Valley ‘Bike Superhighway’ Awarded $14M State Grant

A Caltrans grant brings the 10-mile Central Bikeway project connecting Santa Clara and East San Jose closer to fruition.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Caltrans

City of Fort Worth

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie