Famed landscape architect Lawrence Halprin died this week at the age of 93. Halprin is highly regarded in his field, but in terms of urban planning many of his designs have not stood up to the test of time. Managing Editor Tim Halbur explores his legacy.

RIP Larry Halprin, you were Modernism's Olmsted. Thank you. @svrdesign via Twitter

Lawrence Halprin, a formidable force in American urban design and landscape architecture for more than half a century, passed away this week at the age of 93.

The notion that Halprin was "modernism's Olmsted" has spread among the obituaries, and as a pithy soundbite it is well chosen. Olmsted and Halprin have many similarities: both are highly regarded in the field of landscape architecture, both have made a significant impact on the built environment, and I would argue that both have mixed success when it comes to creating urban public spaces.

Olmsted introduced wilderness into the modern city, resulting in a handful of wonderful parks, most notably Central Park in New York. As Jim Kunstler has noted, he was influenced by the artists of his day including the Hudson River School, painters of dramatic, romantic landscapes of the unspoiled American countryside. The legacy of Olmsted was a persistent idea that parks should mimic the appearance of the natural world, with rolling hills and a sense of nature unconstrained by man.

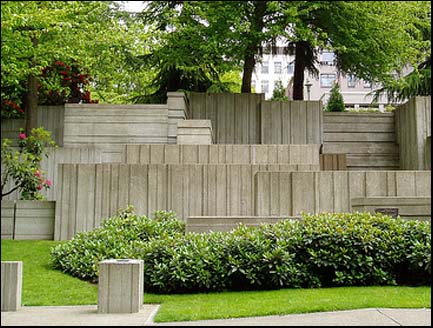

Halprin too was drawn to the grandeur of nature, particularly the dramatic landscapes of the West where he lived and worked. In Portland's Ira Keller Fountain, tremendous waterfalls mimic the glacial scouring of the High Sierras. In his fountain for United Nations Plaza in San Francisco, water was originally set on a timer to recreate the tidal rhythms of the Pacific coast. At Sea Ranch, an enclave of houses on the Pacific Coast and probably his most successful project, Halprin held community workshops on the beach using driftwood to model the way the houses would relate to one another.

Olmsted is sometimes credited with coining the term "the lungs of the city" when referring to urban parks. Whether he wrote it or not, the idea was in the air: cities were viewed as congested places that needed room to breathe. Coming to prominence in the 1960s in San Francisco, Halprin's writings and work show a similar sense that cities are pent-up places and their residents need respite from urban life. He saw public spaces as a means of expression, a canvas upon which the city's residents were free to tell their own story. He was adamant that fountains be open for people to get in the water and play, with no barriers between them and nature.

The public spaces that Halprin designed express the idealism of the 1960s and the struggle characteristic of that era between social control and unfettered individualism. His wife was a dancer, and under her influence he developed a method of graphically 'scoring' the choreography of how people would move through an environment, which he called 'motation'. He was an early proponent of bringing the community into the design and planning process, running creative workshops that today would be called 'charrettes'.

Fred Kent of Project for Public Spaces has been called in to update a couple of Halprin's designs, like Freeway Park in Seattle. A bold statement at the time, Halprin took an unattractive plot alongside an interstate and created a multilevel park. Kent says the design holds up today. "Freeway Park has the formula that we always look for. It has a lot of potential and activities at every level. It needed programming and strong management, but the bones were very good on it. So we were actually delighted with his work."

In other places, Halprin's work has been more problematic. Perhaps society failed to live up to the idealism expressed in some of his designs, or perhaps the designs themselves fell short. Regardless, many of his public plazas, like Heritage Plaza in Ft. Worth, have fallen into disrepair and have been abandoned by the cities they were supposed to engage. Why?

As a graduate student, I conducted a number of post-occupancy observations of Halprin-designed spaces. What I concluded is this: Halprin's spaces often deliberately deemphasize social control, and as a result, they sometimes leave the visitor with a sense of unease, unsure of the rules of engagement.

Halprin's parks and plazas work best in areas where the setting itself compensates for the control and environmental cues missing from the design. Levi's Plaza in San Francisco is tucked away on a corporate campus, and is patrolled by security. The same goes for Halprin's new Lucasfilm campus in the Presidio. To users of these spaces, the plaza is either their place of work or their destination. The majority of Halprin's designs, however, were built in the very heart of the city, and were expected to accommodate all the needs of such a space – gathering place, thoroughfare, lunchtime retreat, concert venue, marketplace, and many more. Many of them failed to meet those needs, and are now closed or being replaced or remodeled just a couple of decades later. "The problem with United Nations Plaza and many of his other designs is that they are for the moment and didn't have a long shelf life," says Kent. "It was more of a design statement, not unlike the iconic architecture we're dealing with today."

Halprin's lasting legacy suggests that he succeeded in changing the way people thought about the aesthetics of the city and what a park, plaza or fountain could be. In this way, he deserves to be an icon of landscape architecture, just as Olmsted is. And yet those same designs in many cases failed to achieve longevity – both because the materials themselves didn't last, and because the design wasn't well-suited to the way people actually use cities today.

As the population of our cities grows and demands more of the urban infrastructure, perhaps we can draw on the spirit of Halprin's creativity and imagination while recognizing that city centers require a level of functionality, longevity and usability that those designs didn't always achieve.

Tim Halbur is managing editor of Planetizen.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

Amtrak Cutting Jobs, Funding to High-Speed Rail

The agency plans to cut 10 percent of its workforce and has confirmed it will not fund new high-speed rail projects.

Ohio Forces Data Centers to Prepay for Power

Utilities are calling on states to hold data center operators responsible for new energy demands to prevent leaving consumers on the hook for their bills.

MARTA CEO Steps Down Amid Citizenship Concerns

MARTA’s board announced Thursday that its chief, who is from Canada, is resigning due to questions about his immigration status.

Silicon Valley ‘Bike Superhighway’ Awarded $14M State Grant

A Caltrans grant brings the 10-mile Central Bikeway project connecting Santa Clara and East San Jose closer to fruition.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Caltrans

City of Fort Worth

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie