As single-family houses become increasingly self-contained units connected to their neighbors solely by well-driven, and rarely walked, streets, Ross Chapin, FAIA author of Pocket Neighborhoods: Creating Small-Scale Community in a Large-Scale World, looks at the ways in which emerging trends in neighborhood design can help rebuild the bonds of community.

Houses are typically marketed on virtues of curb appeal, size, privacy and personal amenities. Realtors list an impressive two-story brick-faced portico, three-car garage and a bathroom with every bedroom. The media room and backyard barbecue round out the amenities, making the home a self-reliant hub of family life.

Houses are typically marketed on virtues of curb appeal, size, privacy and personal amenities. Realtors list an impressive two-story brick-faced portico, three-car garage and a bathroom with every bedroom. The media room and backyard barbecue round out the amenities, making the home a self-reliant hub of family life.

Once new homeowners move in, however, it may take some time for them to meet their neighbors. The street out front is less likely to be a place to chat with a neighbor than a space to travel through by car. Most family activities occur in the privacy of the home and backyard, while world beyond the front door is vacant. This means fewer opportunities to share a favorite recipe, tell about the trip to the lake, or discuss the upcoming mayor's election. Without daily interactions, neighbors are less likely to call on one another to look after a child while out for groceries, or check in on an elderly neighbor when the curtains haven't opened by 10am. When the links among neighbors are weak, the vitality and resilience of a community is diminished.

Over the last 15 years I've actively explored pocket neighborhoods as a typology of housing to counteract these trends. I've come to see how these small-scale communities can be building blocks for a more resilient society.

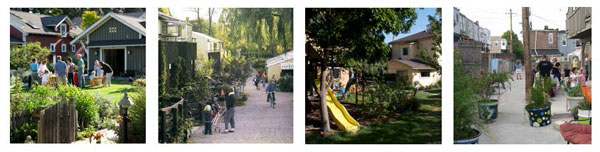

What are Pocket Neighborhoods? Essentially, pocket neighborhoods are small groups of houses or apartments gathered around a shared open space. They might take the form of a garden courtyard, a pedestrian street, a series of joined backyards, or a reclaimed alley. These clusters form at a sub-block scale in a semi-private zone of ownership. Think of them as a neighborhood within a neighborhood.

Pocket neighborhoods exist across all transects - Urban Centers, Urban Neighborhoods, Suburbs, Small Towns and Rural areas. The key idea is that a relatively small number of nearby neighbors share and care for a common space together.

At its core, this is not about aesthetics or style; it's about design that cultivates healthy neighborly connections.

Passersby on a public street might offer glancing nods to one another; in a pocket neighborhood, nearby neighbors are likely to expand a chance meeting into a chat or an impromptu get-together with order-out pizza. They are more invested because they share the passage of time in the same place. And it is the design of the shared space that makes it easier to happen.

Don't get me wrong - the anonymity of urban living can be freeing, and sometimes nosy neighbors can be annoying. But if you're out of commission with a broken leg, it won't be your friends across town or family across the country that will walk your dog every day. It will be your caring neighbor next door.

How about a mom needs help looking after her kids while going for a short errand? Or a neighbor who needs her cat fed while away on vacation? An elderly neighbor who needs help trimming a hedge? In a pocket neighborhood, nearby neighbors are on a first-name basis with one another, the first to notice a need, and the to first call on for assistance. This is why I believe that pocket neighborhoods are primary building blocks for community resilience. They offer the bonds of small-scale community within a large-scale world.

Design Patterns for Pocket Neighborhoods

Pocket neighborhoods will have different qualities and characteristics given their location: an urban apartment building, an infill housing cluster off of a busy street, a cohousing community planned by its residents, or a group of neighbors pulling back their fences to create a commons in their backyards. There are underlying design patterns, however, shared by all pocket neighborhoods.

Clusters of a Dozen Households. A neighborhood might contain several hundred households, but when it comes to pocket neighborhoods, I believe the optimum size is around 8 to 12 households. If a cluster has fewer than 4 households, it looses the sense of being a cluster, and lacks the diversity and activity of a larger group. When the number of households in a cluster grows beyond 12 or 16, some neighbors are too far away to be neighborly, and group decision-making becomes more unwieldy.

Communities of more than a dozen households can be formed by linking multiple pocket neighborhoods, each with control of their own central common space, and connected by walkways.

Shared Common Space. This is the heart of a pocket neighborhood, what holds it together and what gives it vitality. This space may take the form of a garden courtyard, a playspace at the center of a block, a reclaimed alley, or a community room shared by urban apartment dwellers. The commons is neither private (home, yard) nor public (a busy street, park), but rather a defined space between the private and public realms. Residents surrounding this space share in its management, care and oversight, thereby enhancing a felt and actual sense of security and identity.

The function of the commons is to foster interaction among surrounding neighbors in the daily flow of life. Therefore, make it more than a pretty space to look at. Arrange the approach from the car door to the front door so that residents walk through the commons, and orient the active interior rooms so they look onto the shared space.

Corralling the Car. In America, nearly everyone has a car. But cars don't need to dominate our lives. Start first by locating parking areas to be good neighbors: shield parking areas from the street and the commons. Don't let garage doors greet your guests. Whenever possible, locate parking areas so that residents and guests walk through the shared common area. If cars have access into the commons, be sure they are on pedestrian behavior, as in the woonerf street design perfected by the Dutch.

Connection and Contribution.With any changes made to home or garden, make your neighborhood a better place from your improvements. Connect and contribute to the fabric of the surrounding houses and streetscape. This is one of those "both/and" conditions - make improvements to serve personal needs and desires, while also serving the larger community.

Enclosure and Permeability.Enclosed space taken to the extreme is not good, as in gated communities. A shared common space should have appropriate openness or permeability to the surrounding community. A healthy community ‘breathes' with its surroundings. That said, in a dangerous environment like an urban alley, a gate can offer a level of safety to allow surrounding residents to open to the alley.

Eyes on the Commons.Thanks to Jane Jacobs and Oscar Newman for this one. The first line of defense for personal and community security is a strong network of neighbors who know and care for one another. When the active spaces of the houses look onto the shared common areas, a stranger is noticed. As well, nearby neighbors can see if daily patterns are askew next door, or be called upon in an emergency.

Layers of Personal Space.Community can be wonderful, but too much community can be suffocating. On the other hand, with too much privacy, a person can feel cut off from neighbors. Creating multiple ‘layers of personal space' will help achieve the right balance between privacy and community.

At the transition between the public street and the semi-public commons, create a passage of some sort - a gateway, arbor, or narrowed enclosure of plantings. Between the commons and the front door, create a series of layers - such as a border of shrubs and flowers at the edge of the sidewalk /a low fence /private yard / a covered porch with a low railing and flowerboxes /and then the front door. With this layering, residents will feel comfortable being on the porch - enough enclosure to be private, with enough openness to acknowledge passersby.

Where the space is limited, such as an urban apartment, think of the layer just outside the door as a "soft edge", and make room for a bench, or table and chairs.

Layers of personal space continue on the interior of the homes - locate the more active living spaces toward the shared commons, and the more private, personal spaces toward the back of the house and upstairs. Sometimes, having a secluded garden is just what is needed to recharge a busy life. Locate this space at the rear of the dwelling, or on a roof terrace.

Front Porch. The front porch is a particular ‘layer of personal space' that needs highlighting. It is perhaps the key element in fostering neighborly connections. It's placement, size, relation to the interior and the public space, and height of railings is both an art and a science. I wrote more about ‘A Good Porch' on our blog.

Nested Houses.Having a next-door house or apartment peering into your own can be uncomfortable and claustrophobic. Therefore, design residences with an open side and a closed side so that neighboring homes ‘nest' together - with no window peering into a neighbor's living space. The south side of this cottage below opens to its side yard, while the north side of the next house has skylights for daylight, but no windows looking back.

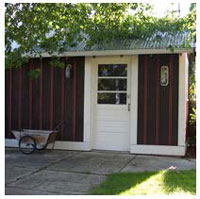

Commons Buildings & Gardens.An advantage of living in a pocket neighborhood is being able to have shared buildings and gardens. The easiest and least expensive amenity is a common tool shed (how many rakes, shovels, hoes and lawn mowers do you need in a close-knit neighborhood?). An outdoor barbecue or picnic shelter is another.

A multipurpose room with a kitchenette, bathroom and storage room can be used to host community potlucks, meetings, exercise groups and movie nights. Larger aggregate communities of several pocket neighborhoods may be able to afford a community kitchen & dining hall, guest apartment, workshop and children's room. And pocket neighborhoods of any size will enjoy the benefits of a community vegetable garden.

Beyond being amenities for residents, these common facilities foster relationships among neighbors and strengthen their sense of community - considered by some as essential ingredients for creating community.

Since we built and sold our first pocket neighborhoods in the Pacific Northwest, cities and towns across the country have been adopting zoning ordinances that provide incentives for this type of development. Planners see this typology as a means of preserving the scale and character of existing neighborhoods while offering a wider range of housing options and affordability. Developers see the approach as a viable infill strategy at a sub-block scale, and organizing pattern for planning at a larger neighborhood scale. Not least, pocket neighborhood homeowners and renters are getting to know their neighbors the way their grandparents did.

Ross Chapin, FAIA, is an architect and author based near Seattle, WA. Over the last 15 years, Ross has designed and partnered in developing six pocket neighborhoods in the Puget Sound region and has designed dozens of communities for other developers across the US, Canada and the UK. Many of these pioneering developments have received international media coverage, professional peer review and national design awards. Ross's book, Pocket Neighborhoods: Creating Small Scale Community in a Large Scale World (Taunton Press), has received wide acclaim, including listing in Planetizen's 2012 Top Ten Planning & Design Books of the Year. For more information: www.pocket-neighborhoods.net and www.rosschapin.com *All images by Ross Chapin, unless otherwise noted

Depopulation Patterns Get Weird

A recent ranking of “declining” cities heavily features some of the most expensive cities in the country — including New York City and a half-dozen in the San Francisco Bay Area.

California Exodus: Population Drops Below 39 Million

Never mind the 40 million that demographers predicted the Golden State would reach by 2018. The state's population dipped below 39 million to 38.965 million last July, according to Census data released in March, the lowest since 2015.

Chicago to Turn High-Rise Offices into Housing

Four commercial buildings in the Chicago Loop have been approved for redevelopment into housing in a bid to revitalize the city’s downtown post-pandemic.

EV Infrastructure Booming in Suburbs, Cities Lag Behind

A lack of access to charging infrastructure is holding back EV adoption in many US cities.

Seattle Road Safety Advocates Say Transportation Levy Perpetuates Car-Centric Status Quo

Critics of a proposed $1.3 billion transportation levy say the package isn’t enough to keep up with inflation and rising costs and fails to support a shift away from car-oriented infrastructure.

Appeals Court: California Emissions Standards Upheld

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the California Air Resources Board, the nation's two most powerful environmental regulatory agencies, won an important round in federal court last week. But the emissions standards battle may not be over.

Barrett Planning Group LLC

City of Cleburne

KTUA Planning and Landscape Architecture

HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research

Mpact Transit + Community

HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research

City of Universal City TX

ULI Northwest Arkansas

City of Laramie, Wyoming

Write for Planetizen

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.